Multi-Game Link Cable Protocol Analysis

Different games will help show different ways the link cable can be used

Expanding horizons #

The research stage of this project has progressed nicely. We understand the Game Boy link cable protocol, have created tools for interfacing with emulators and real hardware, and have even conducted tests over the internet. It’s almost time to start on the full implementation but there are a few open questions to answer first.

So far, the only game’s protocol we have studied in depth is Pokemon generation 1, which turned out to be relatively straightforward. The protocol is symmetric once each game has been put into slave mode: both games contain the exact same state and send the same type of data at the same time. This allows our experimental TCP serial bridge script to be implemented as a naive byte forwarder. Pokemon also fared well over a high-latency unstable internet connection due to its turn-based gameplay.

However, there are a wide variety of Game Boy game genres and it is doubtful that their protocols will all be so simple and latency-tolerant. We want to create a robust implementation to use in place of the test script and hardware but there are several unknowns. How do timing requirements differ across game types? How common are symmetric protocols? How much server-side logic will be needed for this project? Can we keep up with transfer sizes and speeds while maintaining good performance? In order to design and create our full backend server and Wi-Fi adapter, we need to answer these questions. To do so, we will analyze a cross-section of different multiplayer game types in the Game Boy’s library:

- A puzzle game (Tetris)

- Two racing games (F-1 Race and Wave Race), and

- A fighting game (Street Fighter II)

In addition to using an emulator, we can use our previously created tools to monitor link cable transfers on real hardware. The chosen games are all real-time, unlike Pokemon. The level of player interaction differs significantly between them which should give us a good overall idea of the kinds of game protocols that exist (assuming similar games use similar protocols).

Protocol documentation #

While looking for information about how different Game Boy games communicate we noticed that not many of them have been documented online before (at least publicly). Generally only the most popular are documented (e.g., Pokemon). We saw this as an opportunity to build a helpful resource for future projects and have created a dedicated section of this blog to store the inner-workings of game protocols. As we reverse-engineer games, we will create corresponding pages in this new section. Blog posts will still contain protocol information when relevant but may omit low-level details and link to the documentation instead for the sake of brevity and to avoid duplication.

Game analysis #

Tetris #

Not the first game to support the link cable, but the first for many

We already know that it’s possible to support Tetris over the internet because that’s exactly what the project that inspired this one does. Stacksmashing’s original, however, has some limitations: it doesn’t allow difficulty selection or multiple rounds (the game must be reset). It’s possible that the missing features are simply unimplemented due to the proof-of-concept nature of that project, but their omission could also be necessitated by technical restrictions. As such, it’s still valuable to study Tetris’s protocol. At the very least it can serve as a stable “hello world” of sorts as we build the rest of GBPlay, since it is guaranteed to mostly work and we want to support it anyway.

Tetris link cable protocol #

Tetris’ full link cable protocol details are documented here.

This section will only discuss notable aspects and their implications.

It doesn’t take long for our symmetric protocol assumptions to be violated. Immediately after a connection is established, the music selection screen is shown. Here, the master (and only the master) chooses which track will play during each round. The second player only observes the choice as it is being made and has no input. The transmission is not symmetric. In other words, the two games behave differently and send different data. This is problematic for our project because both Game Boys need to be in slave mode to tolerate latency and thereby work over the internet, which means neither will have a way progress in this case. Difficulty selection – which comes after music selection – is only a little better. While selecting, both games send the same data (their current choice) and so naive forwarding of bytes will allow each to properly see what the other is doing. But when it comes time to confirm, only the master can choose to move on and we are again stuck.

To work around the issue, we will instead need to allow configuration of master-only choices ahead of time (i.e., when creating a game lobby) and have our server send the necessary bytes to both games to simulate a confirmation by the master Game Boy. In effect, the server is the master. This explains some of the limitations of stacksmashing’s project, as it solves these problems the same way (music selection is configurable and difficulty is hard-coded to 0). It’s disappointing that not all setup actions will be possible in the game itself, but it isn’t that noticeable at the end of the day since the music is only ever chosen once at the very beginning of the connection (not even if the game ends and a new one is started). There is room for improvement with the difficulty screen though. We can inspect the bytes being transmitted and auto-confirm if there have been no selection changes for a predetermined amount of time – Mortal Kombat cheat code style.

The menus aren’t the only non-symmetric part of Tetris’ protocol. To ensure fairness, both players receive the same set of random tetrominoes and starting garbage lines (depending on difficulty) before each round begins. This data is supplied by the master game and so our server will be required to generate it for online play to work. This is simple enough to implement. Notably, this transfer can handle much shorter delays between bytes compared to those in the rest of the game, which makes sense since the engine does not need spare time to drive the graphics and music here. To take full advantage of this for optimal performance, our server will need to be able to adjust the transfer delay based on game state so it doesn’t wait longer than needed.

When it comes to actual gameplay, the protocol is straightforward and symmetric. Each game repeatedly sends the height of its stack, which is used to update the opponent height indicator and determine when “attack” garbage lines should be added. Like difficulty selection, naive byte forwarding will mostly work here. That is, until the very end, which involves the master game signaling it’s time to move to the round end screen. With both games in slave mode, our server will need to monitor the transmission for the end of the round and trigger the next screen when that happens – acting as the master. The same applies to deciding when to leave the round end screen.

There is one last hurdle with the round end screen itself. The game state – and therefore data transmission requirements – after this screen depends on whether a player has won 4 rounds or not. If yes, both games return to difficulty selection. If no, another round begins. I can see why stacksmashing chose not to implement multiple rounds. Doing so requires keeping track of the score on the server, and his project supports more than 2 players which makes this complicated. In our case, we will be keeping things as vanilla as possible (at least initially) and so supporting multiple rounds is very doable.

Tetris takeaways #

What’s interesting about multiplayer Tetris is that player interaction is really not central to the main game. The two players are essentially just competing to see who can win first, with occasional “attacks” between them. The timing of these attacks is not critical as they are not the game’s main focus. Further, no attempt is made to detect a dropped connection. Both games will continue running if the link cable is unplugged – their view of the other frozen in time.

These qualities make Tetris an ideal end-to-end test game for online play since lag or delayed transfers will not have a significant impact on gameplay. With that said, its protocol certainly breaks the assumptions our current TCP serial bridge tool is based on. It is both symmetric and asymmetric depending on the game’s state and there is data and logic which only exists on the master side. This is quite different from Pokemon’s protocol, which is to be expected because it is a very different game.

Examining Tetris has uncovered several gaps in our understanding, but as we’ve seen, all of them are able to be crossed (albeit some more cleanly than others). Just this one game has made it clear that our backend server will need to be extremely flexible. To work with both symmetric, asymmetric, and hybrid protocols it must be capable of naively forwarding bytes while optionally observing the data being exchanged and injecting bytes of its own. It must support switching between these modes and executing any necessary master-only logic dynamically, depending on the current game state. For settings outside of the slave game’s control, the server must also allow configuration on lobby creation (i.e., via a front-end UI). Finally, to make the most of timing affordances, it will need a way to adjust the data transfer delay when possible.

F-1 Race & Wave Race #

These two racing games (F-1 Race, left; Wave Race, right) are much more complex than they appear

Tetris necessitates a complex backend server on its own but its protocol keeps transfers to a minimum and is very lenient. The two players only occasionally interact. Dropped or delayed data in the middle of a round is tolerated and fairly low-impact. It is important to also consider games with more frequent, high-priority communication. Racing games are good examples. Players can see (and usually drive into) each other, meaning their positions must be constantly exchanged. Analyzing such games will give us a better idea of the latency-tolerance and timing requirements of chattier protocols.

We chose two similar games – F-1 Race and Wave Race – because we noticed early on that data transfer timing was very important, and wanted to ensure this trait was the rule and not the exception.

F-1 Race & Wave Race link cable protocols #

We have not yet fully documented the link cable protocols of F-1 Race and Wave Race since their relevant qualities have to do with how data is sent and received in general, rather than the data itself.

Full documentation will be available when support for these games is added to GBPlay.

Both F-1 Race and Wave Race support the 4-player adapter. For simplicity, we will only consider 2 players for now (incidentally, the 4-player adapter works by communicating separately with each game).

The menu screens of both games have similar restrictions to those of Tetris: only the master Game Boy can confirm, and in some cases select at all. These can be dealt with in the same way as before by allowing configuration of one-sided choices ahead of time and using timeouts to auto-confirm all others (i.e., the name entry menu). Also similar to Tetris is the start position screen. In both racing games, player starting positions are randomized and shown on each Game Boy with a slot machine animation. To ensure synchronization, the actual decision happens on the master game before being transmitted and displayed. This can also be solved relatively easily by generating the start positions server-side.

The largest challenge, unlike Tetris, is that the slave game needs to be constantly receiving data in order to run. This applies not just during menus but also during races themselves. In F-1 Race, everything appears to be driven by the speed of the link cable connection. Delays in communication mean delays in gameplay, and sending data too quickly makes the game run faster than it should. Wave Race is even worse: if nothing is received in ~200 ms then it will return to the main menu! As a result, internet latency will render both games unplayable. However, as we saw with Tetris, player interaction is not actually key to the outcome. Since these are racing games, the core element that matters is detecting the winner and loser, and so supporting them is still possible with some compromises.

Our current network protocol operates at the byte level. A byte sent from the server to the client is interpreted as a byte to send over the link cable to the connected Game Boy, and vice versa. There are no higher-level constructs or abstractions. To address the requirement of fast, constant data transfer we can introduce the concept of command packets, starting with a keepalive packet. This new type of packet can instruct the client hardware connected to the Game Boy to repeatedly send configurable data to a game in between regular transfers. This will allow us to ensure data is received without it having to make a round trip to the backend server every time, satisfying the tight timing window. The server can then periodically poll the client for all of the bytes received from the Game Boy since the last poll (with timestamps), allowing games like F-1 Race and Wave Race to operate asynchronously.

With this scheme, we can solve the slowdown and reset problems. However, there is still the matter of the opponent’s position. This is where the compromising comes in. There is no way to keep these games perfectly in sync over the internet. There is too much latency to meet their timing needs. Keepalive transfers will allow us to send the real location data at slower speeds or even drop it entirely, but that means the opponent’s vehicle on the screen won’t always be up to date. It may appear to suddenly jump to its next position and driving into it could behave erratically. We view this as an acceptable trade-off given that these elements are not the main focus of the games and they are unplayable otherwise. What is important is having a rough idea of where the opponent is located on the course, which will still be the case. One potential improvement is predicting where the vehicle will be on the client-side and sending that data to the game until the true location is received (e.g., assume the player will keep moving straight and not go off-course).

F-1 Race & Wave Race takeaways #

I was surprised by the amount of data these games actually send. To keep tightly in sync and also leave time for game logic they do small transfers, but a lot of them – a worst-case scenario for an internet connection. Their protocols are extremely timing dependent, but luckily most of the data (opponent position) is not relevant to the outcome of the game and this problem can be worked around with some concessions such as janky or out of sync opponent movement.

Again, our assumptions were violated. We built the TCP serial bridge script in a very asynchronous way, when in reality some games are highly synchronous. These games highlight the need for client-side logic on our link cable adapter to send keepalive data and for a higher-level network protocol to configure that logic. None of this is possible with our current setup. We can’t blindly forward bytes or drive the connection with data alone anymore.

Although there are workarounds for the problems these kinds of protocols present, they are just that – workarounds. We now know that GBPlay can’t be perfectly seamless for every game. There will be some which “mostly” work in exchange for functioning online at all. The next game to examine will serve as a stress test to gauge the extent of this: a fighting game.

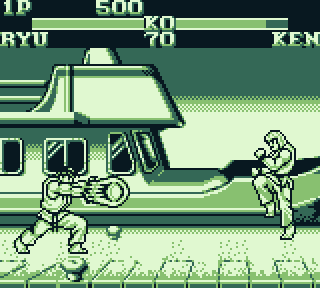

Street Fighter II #

While not the most ideal way to play, this port is still impressive (and Guile’s theme still goes with everything)

Tetris and the racing games have already taught us quite a lot, but they are fundamentally very indirect. Players compete in parallel to be the first to achieve an objective, only interacting superficially (garbage lines in Tetris, view of the other vehicle in racing games). Their interactions are not central to the main goal. Latency issues can be worked around in these types of games because delaying data transfers is tolerable, but what about games where all data is relevant to the outcome?

In fighting games such as Street Fighter II, the end result is solely dependent on the position and state of the other player. Every jump, punch, and block matters. If the two games get out of sync then they may disagree on whether a hit has landed or who the winner is. In the previously analyzed games, interaction is incidental. Here, interaction is the entire point. Analyzing a truly real-time game like this will be the last piece of the puzzle needed to understand what is and isn’t possible with this project.

Street Fighter II link cable protocol #

Street Fighter II’s full link cable protocol details are documented here.

This section will only discuss notable aspects and their implications.

Like the racing games, Street Fighter II needs to constantly receive data in order to run. It is most similar to F-1 Race in this regard: if it receives nothing it will freeze rather than reset. Other than this, the menus are surprisingly simple. Both games behave mostly identically and are allowed to select and confirm! The only departure from this is the occasional need for the master game to initiate synchronization transfers when entering the first menu and starting a round. These constraints can be worked around as with the other games analyzed by using keepalive transfers and monitoring the connection to inject bytes when necessary. Other than that, naive byte forwarding will work in theory. In practice, it is not so easy.

The reason why byte forwarding is all that is needed for most of the game is because Street Fighter II’s protocol operates by constantly exchanging joypad input. This keeps things extremely simple. It is as if each player is using a second controller connected to the opponent’s Game Boy, allowing the game to re-use much of the single-player code. Unfortunately, this also introduces the same problem as the racing games: the internet is too high-latency to send the joypad input at playable speeds. The game will work, but it will be very slow. Unlike before, we cannot delay, drop, or generate data to get around this since every button press is integral to the game’s outcome. Both simulations must be exactly in sync.

Modern online games handle this problem and compensate for lag by either delaying inputs or, more commonly, using client-side prediction and rewinding. Each game makes educated guesses about what other players will do and runs normally to avoid lag. If the predictions turn out to be incorrect when the opponent inputs are received, the game re-simulates the corresponding period of time using the real actions that actually occurred instead of the predicted ones. This is all invisible to players, who only see the final result. Neither delay nor rollback techniques are feasible for Street Fighter II because there is no way to modify or rewind the state of the game without using hardware mods or creating a custom, latency-tolerant version of the game itself. The hardware and software are fixed.

Hypothetically, even if an internet connection had low enough latency to transfer the joypad data fast enough, there would still be problems due to the protocol’s simplicity. For instance, each game detects when the round is over on its own. There is no “round end” byte sent over the link cable because there doesn’t need to be – each game is simulating the exact same thing. If we wanted to support multiple rounds in this scenario we’d have to emulate the game on the server and read its memory to detect when it’s over and who won. This problem could technically exist for any type of game. For Street Fighter II we could compromise and only allow one round, but this is all quickly getting away from our goal of seamless online play. With this and the more fundamental issues in mind, it’s fair to say that properly supporting games like Street Fighter II at reasonable speeds – let alone over the internet at all – is well and truly infeasible for this project. It is easy in theory, but unplayable in practice.

Street Fighter II takeaways #

Unfortunately, truly real-time games like Street Fighter II have too much overhead to work well online. The sheer number of transfers cannot be supported effectively given the latency of the internet. Lag matters. The game will run far too slowly and there is no way to implement lag compensation strategies without modifying the hardware or the game. Going beyond a plug and play solution that works on an unmodified Game Boy is not the goal of this project. We want to build something that is compatible with 1989 hardware out of the box. The impact of lag is not entirely surprising given that quality online play is a problem fighting games face even today.

These issues will exist for any real-time game where interaction is the main focus. If the key element to the outcome is player action and it needs to be synchronized often without the possibility to delay, then an internet connection is simply too slow. Consequently, GBPlay will not be able to support the entire Game Boy library – even partially with keepalive workarounds like the racing games. Truly real-time games are infeasible. This is unfortunate but somewhat expected given the anachronistic nature of this project. Multiplayer Game Boy games weren’t designed for the internet, especially the internet of the era. They were designed for the fast, real-time communication that a hard-wired physical connection delivers.

On a more positive note, we have seen that many Game Boy games are not this demanding when it comes to timing needs. Part of the reason is hardware limitations. The serial link and CPU are slow and game code cannot run while link cable data is being prepared or processed. Larger and more frequent transfers mean less time to run game logic. In general, we expect that we will still be able to support a large number of games based on what we have seen so far.

Conclusion #

To answer the questions posed at the beginning of this post: timing requirements can differ both within and across games, a given protocol may use any combination of symmetric and asymmetric transfers depending on state, server-side logic will absolutely be needed for a majority of games, and workarounds (including client-side logic) are sometimes required to maintain playable speeds.

We also learned the extent to which different games will work online. They fall into three broad categories. Turn-based games such as Pokemon are ideal due to their symmetric nature and because the natural delays between actions make lag less noticeable. Indirect real-time games like Tetris, F-1 Race, and Wave Race – where players are merely competing in parallel – will generally work well enough since interaction is incidental and data can be delayed or dropped without much impact. Sometimes these will require compromises. Finally, fully real-time games such as Street Fighter II use all player activity to determine the outcome and are therefore infeasible to support due to the amount of transfers and the impact of latency. It is also not always possible to determine their complete state.

Our server cannot be fully game-agnostic like we hoped, but we can make writing game-specific code easier with high-level abstractions. Through our multi-genre analysis we now have a much clearer picture of the different usage patterns we must handle, and consequently the features our server needs. Investigating a variety of protocols also has us confident that new assumption-breaking surprises will be few and far between. With this in mind we can now create a stable, future-proof backend server and Wi-Fi adapter to use instead of the existing TCP serial bridge script and Arduino-based adapter.