Beyond Serial: Linking Game Boys the Hard Way

Linking Pokemon games through a PC

Putting all the pieces together #

In the last post, we talked about building a USB to link cable adapter and using it to send data to an original Game Boy via a PC. With the adapter, data can be sent both programmatically (to implement game protocols ourselves) and using an emulator (to link with arbitrary games for testing). However, there’s still one major piece missing: a second Game Boy!

Our existing tools allow testing via emulation, and with one real Game Boy. The former is useful for gaining a high-level understanding of game protocols, and the latter can help verify timing requirements and hardware behavior under non-standard conditions. But the entire point of this project is to link two real devices together. Now that we have the ability to communicate with Game Boys individually using the USB adapter, it’s a good time to try forwarding data between them.

We’ll start with a hard-wired connection through the same PC, which should be around the same speed as previous one-sided tests. After that, we’ll attempt a LAN connection, where there may be some noticeable latency. Finally, we can try it over the internet – the first full GBPlay proof of concept!

Connecting Game Boys through a PC #

Connecting two Game Boys directly is actually very straightforward: just use the link cable! Joking aside, building on our current one-Game Boy communication setup to mediate data transfer between two devices is simple in theory. We just need to use two adapters to receive a byte from one console, send it to the other, then repeat the process in the opposite direction.

There’s one caveat: since both Game Boys need to be in slave mode in order to tolerate latency, forwarding bytes blindly from the start won’t work. Both games will be trying to determine which mode to operate in, so we’ll have to first send the proper game-specific initialization data to get each to accept an external clock signal from the USB adapter. This wasn’t required for the emulator to Game Boy connection because the emulator could act as the master device and slow down or speed up as necessary to maintain the connection. Once both Game Boys are in slave mode, naive forwarding should work and the games themselves should take care of the rest. Sending bytes one at a time will make any connection latency more noticeable due to the increased per-byte overhead. However, doing so allows the large majority of link cable communication to be treated as a black box, simplifying the implementation. We want to do the bare minimum to get the connection set up and then just act as a messenger.

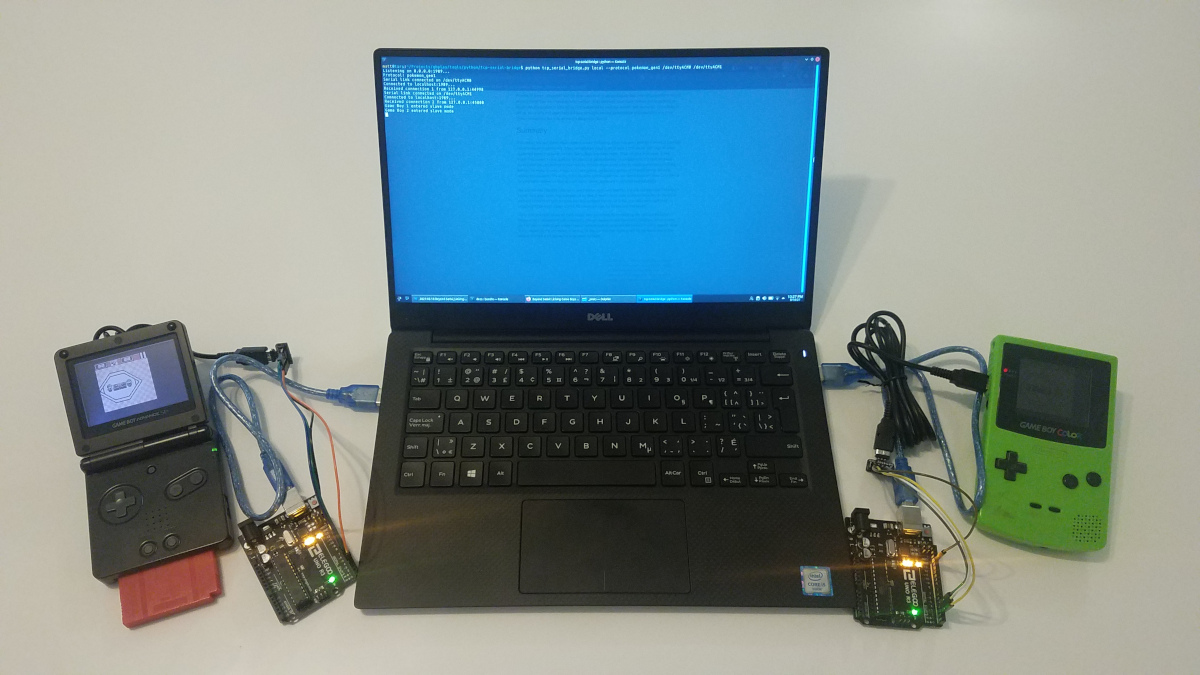

Connecting two Game Boys through a PC using our Arduino-based USB to link cable adapters

For these initial two-Game Boy connection tests, Pokemon Generation 1 was used since we already understood its protocol well. A new “serial bridge” script based on our existing serial link cable client class was created. It takes as input the serial port for each link cable adapter, as well as the game that’s being played (so that the appropriate initialization data can be used). Only Pokemon is supported for now. The script instantiates a client for each Game Boy and waits until the connections are opened before continuing. After both handhelds are connected, a setup function corresponding to the game that was specified at launch is called for each one. This function takes the last byte received from a Game Boy and returns the next initialization byte to send to it, or null when setup is complete (i.e., the device is in slave mode). This is similar to the way the callbacks in our other test scripts work. The logic of the setup code is decoupled from the mechanism by which the data is sent, allowing the code to be simpler and the data to potentially be sent anywhere (an emulator instead of real hardware, for instance).

Once each Game Boy is in slave mode, the script forwards data between the two handhelds in a loop, acting as an intermediary. Since one transfer both sends and receives a byte at the same time, the very first byte to send needs to be generated by us. For this, the script just uses the last byte received during initialization, although it could have also faked it because the beginning of the connection is protocol-specific anyway. During this time, we can also easily sniff the connection and log the data. Intercepting communication was already possible when using an emulator but now we’re be able to spy on the original hardware, which will be useful as we adjust the timing to attempt to minimize latency and push the limits of the link. If garbage data is being sent, it’ll be easy to see. In fact, the capability was used when debugging the new script.

Doing things this way works well and there’s minimal overhead. For comparison, with a direct connection between Game Boys it takes about 4 seconds to transfer Pokemon trainer data (424 bytes). When sending the same data using 2 USB link cable adapters and a PC it took 6 seconds. Not too shabby. The code for the serial bridge script is available here. Below is a video demonstration of a Pokemon battle between two Game Boys connected through a PC.

A Pokemon link cable battle between two indirectly connected Game Boys

This isn’t a general solution. The fact that game-specific data is needed is unfortunate, but with Pokemon at least, it doesn’t take much to get the games into the proper mode (just one byte). This method also assumes that once games are properly initialized, they’ll be able to operate correctly with byte forwarding alone and no further intervention. That is, it assumes that each game has the same state information and sends the same type of data at the same time – a so-called “symmetric” protocol. Things may not be so easy across the board, so more testing is required with different types of games. Depending on the conventions used by other games and how similar they are to Pokemon’s, we may be able to get away with a semi-generic approach which uses a common implementation with configurable initialization steps for each specific game.

Networking Game Boys #

Connecting two Game Boys together through the same PC worked well with minimal tweaking, which was very encouraging. The logical next step was extending it to work through two different PCs. At a basic level, the serial bridge script is just sending and receiving bytes. It uses our link cable client helper class and doesn’t directly depend on where bytes come from or go. Supporting a link across different PCs was therefore a matter of just transferring bytes over the network rather than a link cable.

To do this, the serial bridge script was split into two parts: a client and a server. The server handles the initialization and forwarding logic. Instead of sending and receiving data to and from serial ports, it does so over TCP sockets. Clients handle the actual Game Boy communication. They simply wait for a byte from the server, send it to the USB link cable adapter’s serial port, and then send the response back to the server. Very little has changed from what was there before aside from the extra layer of abstraction. If a server process and two client processes are run on the same PC, there’s no visible difference at all (which is very convenient; no separate script needs to be created for local testing). The updated TCP serial bridge script is here.

LAN connection #

With the updated script in hand, the server and one client were run on one PC connected to the first Game Boy, and another client was run on a different PC connected to the second Game Boy. The server PC was connected to the network via an Ethernet cable, and the other used 802.11ac Wi-Fi. Below is a video of a Pokemon battle over my home network.

A Pokemon link cable battle between two Game Boys connected over LAN

Instead of taking 4 seconds like real hardware, transferring Pokemon trainer data took 13 seconds. Not great, but not terrible either. While acceptable, the ~2x increase in time compared to the single-PC connection had me worried about how slow an internet-connected link would be. I was concerned that games would be effectively unplayable online.

Internet connection #

At the time of these experiments, I didn’t have someone else to test with over the internet (Aidan was in the middle of a move), so for simplicity I connected the second PC to the internet via my phone’s mobile data connection instead of Wi-Fi. Cell service isn’t great in my area, and I was also doing all of this in my basement (which seriously degrades the signal). I tested the connection latency by pinging Google and the round trip time was about 500 ms or so on average, and sometimes climbed as high as 2000+ ms. For reference, on my home network I can get a round trip time of 15-20 ms when using Wi-Fi, and about 10 ms when directly connected to the router.

So, with one Game Boy on my terrible mobile data connection I tried again and the Pokemon trainer data transfer took 77 seconds – just under 13x slower than the single-PC link. This is about how long it took for the mock trader script to run with real hardware before the USB adapter’s send delay was reduced from 100 ms to 5 ms. The data size is known (424 bytes), and so the speed can be calculated: about 5.5 bytes per second. While a little disappointing, there’s a silver lining: my mobile data connection is likely a worst-case scenario, and with that in mind this was a good stress test. The connection was unstable and had frequent latency spikes during the transfer but no data was lost or corrupted. The two games handled the carrier pigeon-grade delays with no issues and after the data was transferred, they behaved as normal. So while the numbers aren’t ideal, they provide reassurance that GBPlay isn’t completely infeasible. Further, regardless of connection quality I suspect that many games won’t need to send this much data all at once (real-time games, for example). If they do, it’ll likely be at the very beginning of the session since there isn’t much CPU time for game logic when sending large amounts of data at decent speeds. In fact, all subsequent transfers in Pokemon after the trainer data are only a handful of bytes long and don’t happen nearly as frequently, so the slowness wasn’t noticeable when battling or confirming a trade. This is another reason to analyze the link cable protocols of different types of games now that we know the connection works online.

In terms of speed, bandwidth isn’t the killer, latency is. Even particularly bad internet connections should perform better than my mobile data connection. They generally have lower latency and regardless of bandwidth, the amount of data being sent is dwarfed by what the modern web demands. Once Aidan is set up, re-running this experiment will give us insight into the performance characteristics of a more typical connection. For now we have a likely upper bound.

Takeaways #

Connecting two original Game Boys together in several different configurations was very motivating! It showed that this project is viable and also gave us an idea of backend implementation requirements. There will definitely need to be at least a little server-side logic for each supported game in order to put both Game Boys into slave mode. What remains to be seen is how much else. The answer to that question will affect the generalizability of our approach. If it can’t be easily generalized, we can attempt to minimize the amount of per-game code by creating common primitives that can be re-used. Analysis of more games – particularly games of different genres – will help make things more clear. The ability to log the data sent between devices will allow us to form a very confident answer compared to emulation alone, especially in non-standard situations like this.

We also learned valuable information about performance and stability. The internet test wasn’t ideal but it served as a good stress test and gave us an idea of what a worst-case scenario looks like. In the future we’ll test with a more typical connection and compare the results to the other data we’ve gathered. Hopefully it’ll be much closer to the LAN link speed than the mobile data link speed.

We’re now at a point where we have a fairly solid set of tools for prototyping. We can use the TCP serial bridge script to experiment with networking different games on real Game Boy hardware, which is what we’ll do next in order to get a better idea of network requirements and the amount of game-specific code that’s needed for the connection to work at all. We can also start looking into the hardware side of this project and how it will connect to what exists currently.